Celebrating 100 years of the Bowling Green

Clifftown & It’s People 1925 - 2025

6th September - 7th October 2025

In 1925 the first bowls games were played on Alexandra Bowling Green. A century later, the green still sits within the heart of Clifftown, surrounded by its terraces and squares. This exhibition brings to life the stories of those who lived, worked, and played here.

By the 1930s bowls had become a cherished pastime. Alderman Parren, founder member of Alexandra Bowls Club, helped establish the Municipal Greens Association, ensuring the sport thrived across Southend. The Pavilion too has always been central, offering refreshments to bowlers and spectators alike. At that time, visitors could even take their tea on the roof. During the war years, the green carried on under the watchful eye of the ARP Warden, providing a sense of normality in uncertain times.

Today, thanks to the efforts of the Clifftown Conservation Society and with support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, we celebrate the centenary of Alexandra Bowling Green by honouring not only the game itself, but the characters who are integral to the heritage of the Clifftown Estate and Alexandra Bowls Club. Through their lives, ambitions, and memories, we reveal how Clifftown has always been more than houses, streets, squares and a bowling green: it is a place of resilience, humour, and belonging.

As we mark this centenary, we look back with pride.

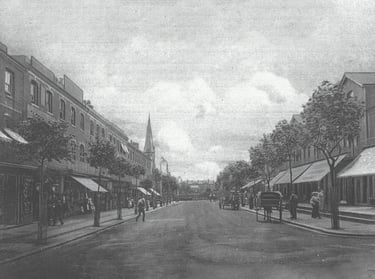

1.Nelson street (The original High Street)

Built in 1860 as part of Clifftown’s first phase of development, Nelson Street quickly became Southend’s main shopping street before the High Street was established. By 1925, as the nearby bowling green took shape, the street bustled with activity. Drapers and hosiers displayed fabrics and fashions; ironmongers and boot makers sold practical wares; while bakers, poulterers and wine merchants tempted shoppers with food and drink.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Colin Cooper)

The People of Clifftown

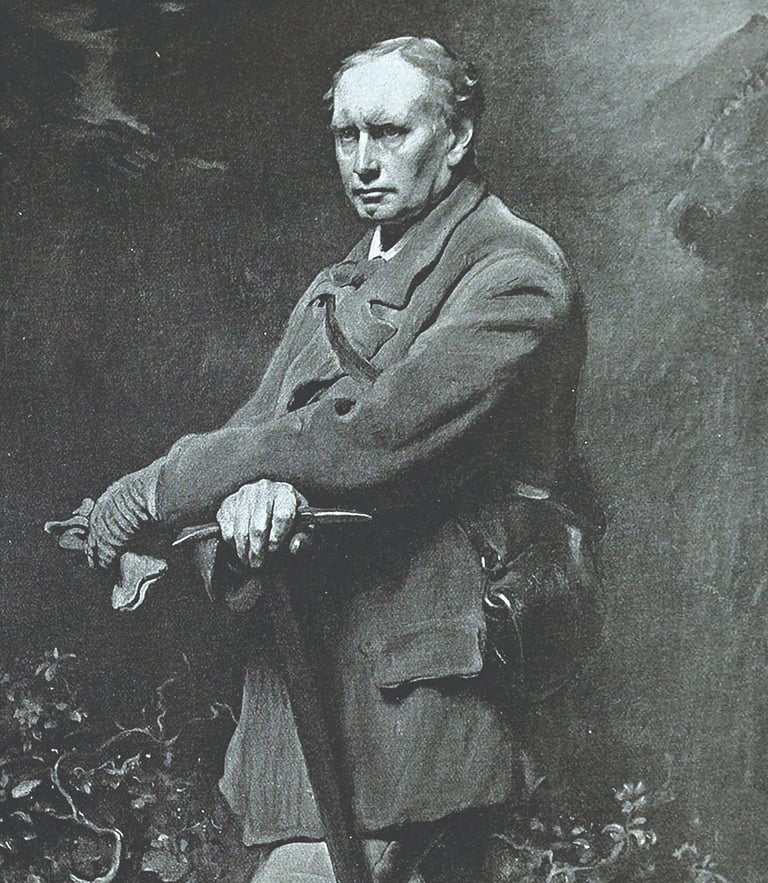

2. Charles Barry Junior (1823-1900) Clifftown Architect

Charles Barry Junior, who designed the Clifftown Estate with Robert Richardson Banks, ensured the houses sold in 1871 were set to enjoy views of the sea. Earlier in his career he had worked alongside his father, Sir Charles Barry, on the Palace of Westminster, before establishing his own reputation with major projects such as Liverpool Street Station and Dulwich College.

(Painting by Lowes Cato Dickinson 1880)

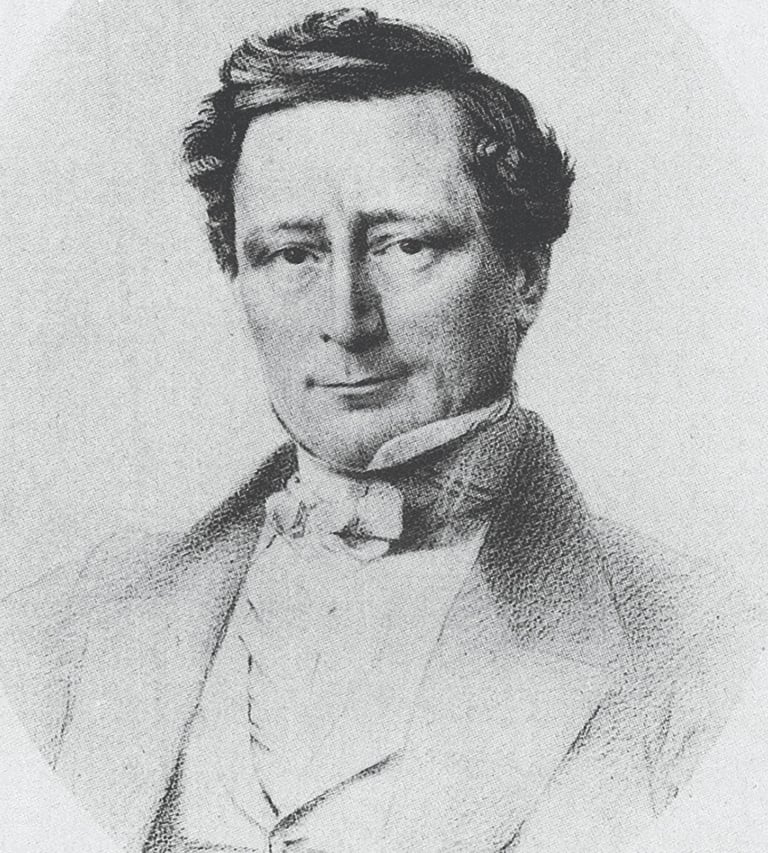

3. Sir Samuel Morton Peto (1809-1889) Civil Engineer responsible for construction of Clifftown

Sir Samuel Morton Peto was a leading civil engineer and railway developer, instrumental in building the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway with Banks and Brassey. Beforehand, as a partner in Grissell and Peto, he oversaw major projects including Nelson’s Column. A once successful engineer and Member of Parliament, his career ended in financial ruin, and he died penniless.

(Engraving by an unknown artist c1850)

4. Thomas Brassey (1805-1870) Civil Engineer responsible for the construction of Clifftown

Thomas Brassey was one of the great civil engineering contractors of the 19th century. Responsible for building many railways, including the London, Tilbury and Southend Line, and part of Joseph Bazalgette’s London sewerage system. Over his career he worked with leading engineers such as Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. When he died in 1870, he left a fortune equivalent to over £750 million today.

(Sketch by Frederick Piercy 1850)

5. William Joshua Cooper, the founder of W J Cooper (1887 - present day)

W. J. Cooper and his family moved to Southend in 1887, establishing themselves as painters and decorators. William continued the business through the First World War before passing it to his son, William John Cooper. Family life and work went hand in hand, even the family dog, Bob, is remembered in their story.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Colin Cooper)

6. The Cooper Family (1954)

W. J. Cooper has remained a family-run business, working on the houses of Clifftown and the surrounding area. In 1946, after returning from the forces, William Walter Cooper, Frederick John Cooper, Geoffrey Cooper and their uncle Frederick Foster purchased the firm from William John, continuing it as W. J. Cooper & Sons.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Colin Cooper)

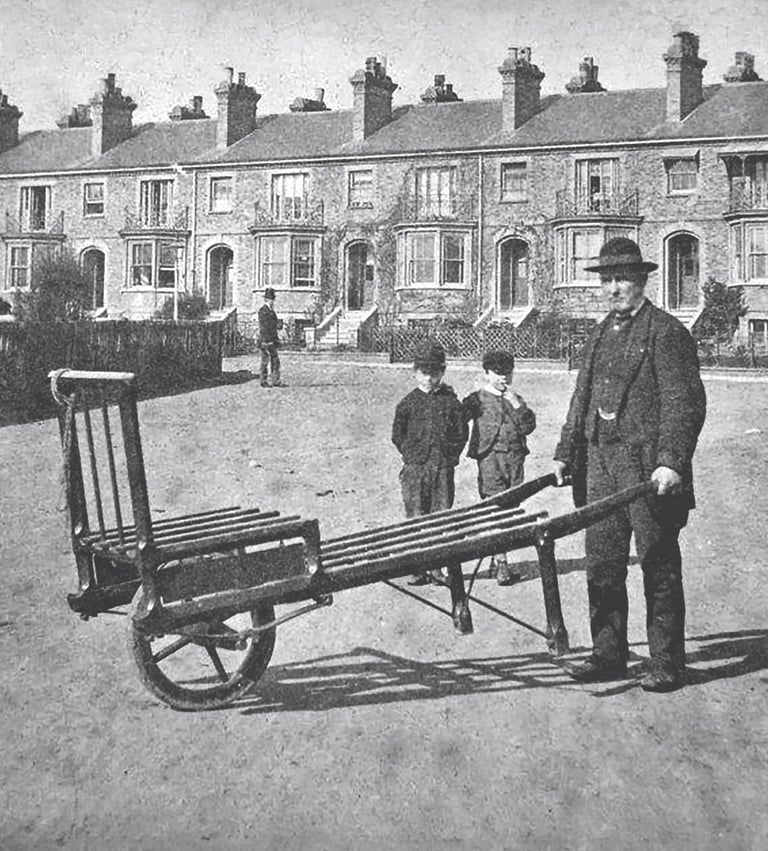

7. Nursery Barrow Man (Date Unknown)

Outside Young’s Nursery near Nelson Street, around 1900, a man pauses with his empty barrow as two young boys look on. Was he delivering goods, collecting supplies, or simply taking a break? Though their names are lost to time, their presence offers a glimpse into the everyday lives that shaped Clifftown long before the bowling green.

(Unknown photographer c1900)

8. Cambridge Road (Date Unknown)

Over the years, W. J. Cooper & Sons have worked on many houses around the Bowling Green. In 1947 their day book records repairs at No. 3 Cambridge Road, from balcony woodwork and sash windows to plastering, for the sum of £154-6-1 (pounds, shillings and pence). They later commissioned the first replacement balcony railings for No. 7 Capel Terrace and carried out extensive roof repairs in Cashiobury Terrace after the gales of 1987.

(Image reproduced courtesy of David Kitchiner)

9. Devereux Road (Date Unknown)

The west side of Devereux Road was built in 1860 as part of the first stage of the Clifftown estate. Originally known as Devereux Terrace, it marked the early growth of the new development.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

10. Ronnie & Rose Wolfe (1953) 16 Devereux

Ronnie and Rose Wolfe lived at No. 16 Devereux Road, marrying in Southend in 1953. Born Harvey Ronald Wolfe-Luberoff on 8 August 1922, Ronnie went on to enjoy a long and successful career as a comedy scriptwriter. Beginning in the early 1950s with radio programmes such as Starlight Hour and Educating Archie, he later formed a writing partnership with Ronald Chesney. Together they created a string of hit television and film productions, including The Rag Trade and On the Buses. Ronnie Wolfe died in London on 18 December 2011, aged 89, three days after a fall in a care home.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Indigouk)

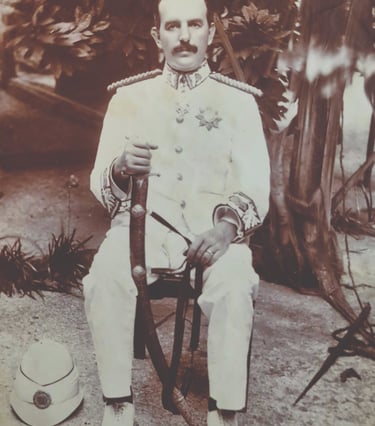

11. Captain Arthur Le Page Agnew (1925) 67 Alexandra Road

In 1925 Captain Arthur LePage Agnew made his home at No. 67 Alexandra Road, bringing to Clifftown the legacy of a life shaped by the sea and empire. After service in the Royal Navy, he worked with the Imperial British East African Company, and in 1893 married Sarah Catherine “Kate” Granger in Zanzibar, where they began their family. Agnew later settled in Wiltshire, where he died in 1941 aged 79, and was laid to rest in Porton.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Garry Stone)

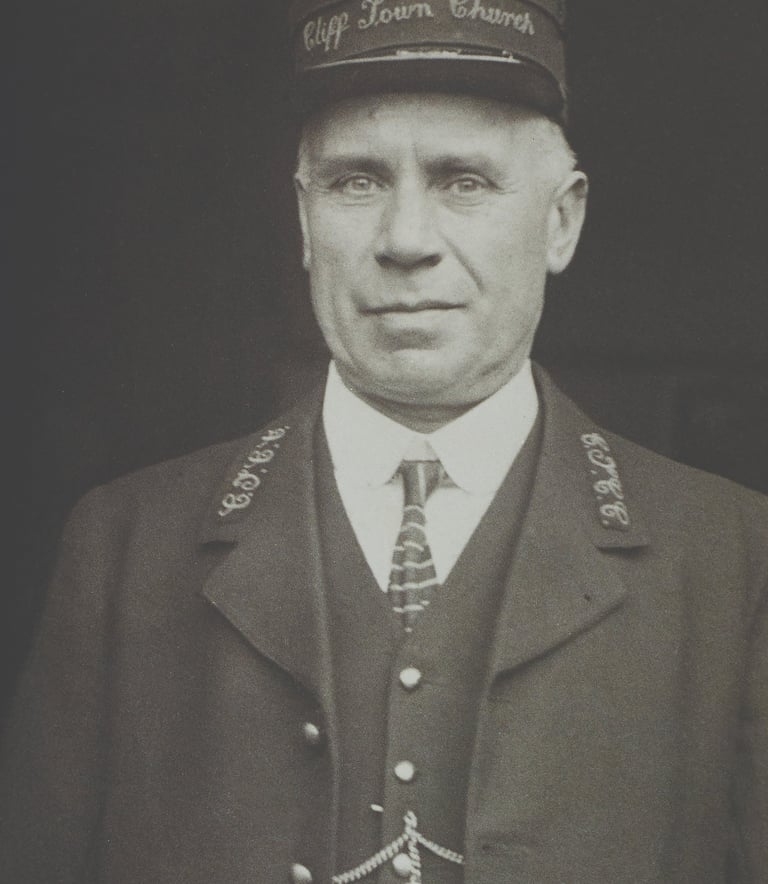

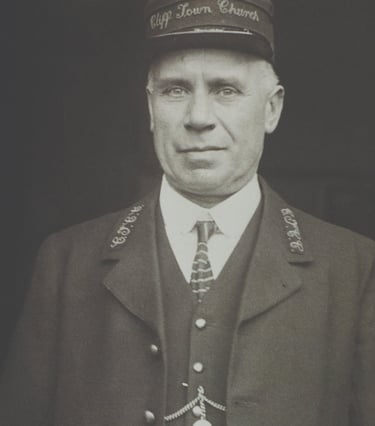

12. Edgar Arscott (1925) Congregational church Caretaker

As caretaker of Clifftown Congregational Church, Edgar Arscott tended the daily life of the Gothic landmark, keeping its doors open to worshippers and the community it served. Married to Caroline Mary Ann Schooley, he lived most of his life in Southend, where he died in 1953 at the age of 86. His story reflects the often-unsung role of those who maintained the buildings at the heart of community life.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office TS-395/1)

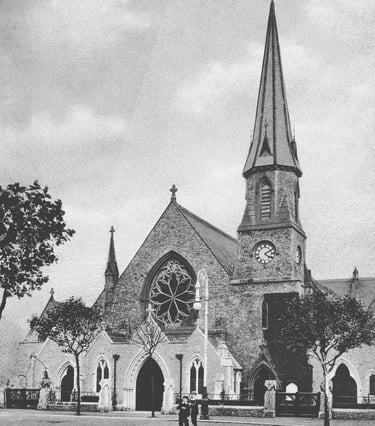

13. Clifftown Congregational Church (1865)

Clifftown Congregational Church, designed in 1865 by William Allen Dixon, was built in the Gothic style as a striking landmark for its community. Once alive with worship, it fell silent in the late 20th century before being transformed into the Clifftown Theatre in 2007. Today, as the home of East 15 Acting School (University of Essex), the building continues its story as a place of gathering, creativity, and performance.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D/DS 206/249)

14. Alan & Margaret Tilley (1925), 3 Capel Terrace

In 1925 Alfred and Gladys Tilley lived at No. 3 Capel Terrace with their three-year-old son Alan and Gladys’ mother, Sophia. Alfred worked as a produce agent, but died in 1928 at the age of 57 after a head injury sustained while playing ball with his son. Alan Gordon Tilley in 1939 then married Margaret Agnes Isabel Evans, only to be conscripted soon after. Captured in Singapore in 1942, he was forced to work on the notorious Burma Railway and survived to live to the age of 90. He died in Southend on 26 January 2008.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Cheryl & Emma Masterson)

15. Capel Terrace (1914)

Capel Terrace was built in 1860 as part of the first stage of Clifftown’s development. Like other terraces in the estate including Cashiobury, Runwell, Devereux and Prittlewell Square. The houses were set at an angle to the cliff, giving every home a view of the estuary.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Colin Cooper)

16. John Charles Herbert (1925) Pier Master, 6 Capel Terrace

In 1925, John Charles Herbert lived at No. 6 Capel Terrace with his wife Jessie Susannah, a short walk from his work as Pier Master. Responsible for the smooth running of Southend Pier from overseeing passengers and steamers to ensuring safety on the world’s longest pleasure pier. Herbert’s role anchored local life to the rhythms of the pier and the estuary beyond.

(Reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D/DS 169/1)

17. Runwell Terrace

The eastern side of Runwell Terrace was built in 1860 as part of the first stage of Clifftown’s development. The western side, shown as public gardens in early plans, was not built until around 1891. Among its residents were Dr George W. Deeping, who helped establish Southend’s first public hospital, and his son, the novelist George Warwick Deeping. Reverend Benjamin Waugh lived at No. 4. He was a social reformer whose campaigning led to the creation of the NSPCC, an achievement marked today by a blue plaque.

18. Benjamin Waugh (1839-1908) Social Reformer, 4 Runwell Terrace

Reverend Benjamin Waugh, who lived at No. 4 Runwell Terrace, was a social reformer and founder of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) in 1884. Under his leadership, the organisation became a national movement, giving a voice to vulnerable children and campaigning for their protection. He was also instrumental in securing new laws on children’s rights.

(Unknown photographer c1900)

19. George Warwick Deeping (1877-1950) Novelist

George ‘Warwick’ Deeping, the son of Southend doctor George W. Deeping, grew up in the town, living at Prospects Place opposite the Royal Hotel and later at Royal Terrace. Although he studied medicine at Cambridge and briefly practised as a doctor, he went on to become a prolific and popular novelist. His best-known work, Sorrell and Son (1925), was an international bestseller, later adapted for stage, film and television.

(Photograph taken for Planet News 1932)

20. The Last Stage Coach before the Railway (1856)

The arrival of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway in 1856 transformed travel to the town, signalling the end of the stagecoach. This image captures one of the last to run in Southend, kept on for pleasure outings when the age of steam had already taken hold. Before the railway, coaches rattled out daily from the Ship Inn and the Royal Hotel to Aldgate, with local operator Charles Woosnam among those driving the route.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Museums)

21. Donkey Ride Stand (1910-1912)

In the years before the First World War, holidaymakers in Southend could take donkey rides run by the Sharp family from their stand at the corner of Cashiobury Terrace and Alexandra Road. Unlike the stagecoaches, which vanished with the coming of the railway, donkey rides endured as part of the Victorian seaside tradition. They reflected the era’s passion for sea air, health, and recreation that drew many visitors to Clifftown and encouraged some to settle here. The donkeys remained a familiar sight into the 1920s, long after the stagecoach had gone.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Keith Brooker)

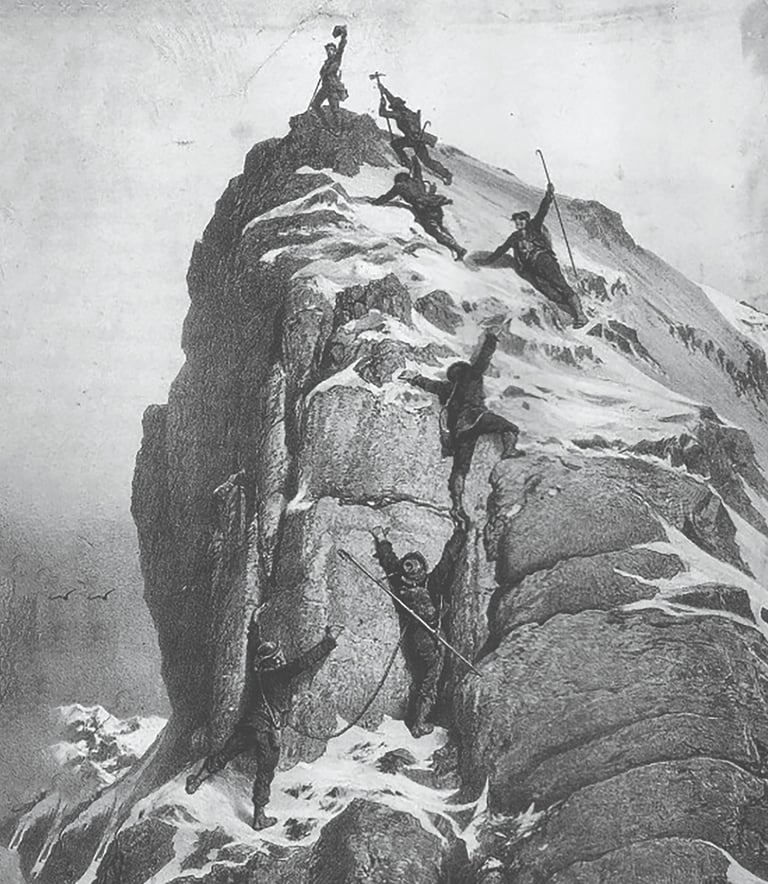

22. Matterhorn Mountain (1865)

The Matterhorn, one of the most dramatic peaks in the Alps, straddles the border of Switzerland and Italy and rises 4,478 metres above sea level. Its first successful ascent in 1865 was made by Edward Whymper of Clifftown Parade, marking a turning point in the history of mountaineering.

(The Matterhorn Ascent - Illustration by Gustav Doré)

23. Edward Whymper FRSE (1846-1911) Mountaineer, 4 Clifftown Parade

Edward Whymper, who lived at No. 4 Clifftown Parade, was an English mountaineer and explorer best known for the first successful ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. His later journeys included explorations in Greenland, which contributed to the development of Arctic research. Whymper also designed a tent specifically for alpine conditions, a design still in use today. From Clifftown to the Alps, his life reflected the Victorian spirit of exploration.

(Painting by George Lance Caulkin 1884)

24. Clifftown Parade (Date Unknown)

Clifftown Parade was built between 1859 and 1861 as part of the first phase of the estate, set high above the estuary with commanding views across the Thames. Its elegant terraces quickly became desirable addresses, attracting professionals, artists and adventurers. Among its residents was mountaineer Edward Whymper, who in 1865 made the first ascent of the Matterhorn. Today the Parade remains a defining feature of Clifftown’s historic seafront.

(Image reproduced courtesy of David Kitchiner)

The Bowling Green

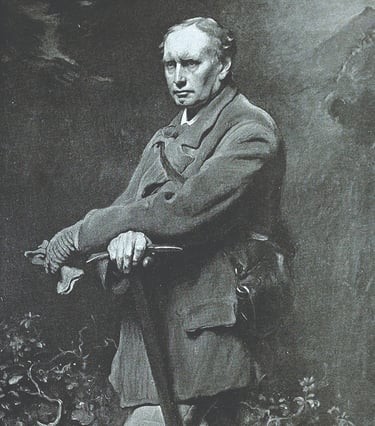

1. Etching of the proposed Clifftown Estate (c1850)

This etching of the proposed Clifftown Estate, produced around 1850, shows the vision that soon transformed the area. In 1859, developers Peto, Brassey and Betts leased land from the Lord of the Manor, Daniel Scratton. Commissioning architects Banks and Barry, fresh from working on the Houses of Parliament, to design a Victorian estate of 124 houses. Built by Charles and Thomas Lucas, the homes quickly attracted interest. The first resident was Ellis Kerry, Southend’s Station Master, with neighbours including Robert Absalom, bathing machine owner, and piano maker Stanley Rudd. Clifftown soon became a fashionable new district, combining sea views with elegant design.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D-DS 314-3-4)

2. The Nursery (1905)

This 1905 image shows Young’s Nursery, which once occupied the site of the bowling green. For a time the land was used for allotments, but in 1922 Southend’s Town Planning Committee voted to end these holdings and transfer the site to the Entertainments and Parks Committee. Plans for a new bowling green and pavilion were submitted by the Borough Surveyor later that year, with construction estimated to cost £4,000. By 1923 work was under way to transform the nursery ground into a space for recreation, part of a wider movement to provide leisure facilities for a growing seaside town.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

3. Laying the turf at Alexandra Bowling Green (1924)

This 1924 photograph shows workmen laying the turf for Alexandra Bowling Green. The contract had been put out to tender the previous November, with the winning bid submitted by Maxwell M. Hart of Glasgow for £2,378 11s 5d. Following discussions with Southend Bowling Club and Essex Bowling Club, the size of the green was altered from 40 yards square to 42, a change that was duly carried out. We have no record of the employees’ feelings, but the image captures the labour behind a space that would soon become central to Southend’s bowling community.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D-BC-1-4-10-27-104)

4. The Telephone Box (1924)

In May 1924, the Post Office Engineering Department was granted permission to place a telephone kiosk at the south-east corner of the new bowling green. For many decades it served the community before falling into disuse and disrepair in the early 2000s. In 2019, the Clifftown Conservation Society, together with local residents and support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, raised funds to restore the box, transforming it into the Clifftown Telephone Museum, one of the smallest museums in the world. Today it hosts exhibitions by local artists, with an audio guide voiced by Dame Helen Mirren, celebrating the heritage of Clifftown.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D-BC-1-4-10-27-103)

5. The Opening of the Bowling Green (1925)

The inaugural match at the bowling green took place in 1925 between players from Southend and Essex Bowling Clubs, with the Central Banqueting Hall Orchestra providing a musical interlude. Charges for use of the green were set at 6d per player per hour, including the use of one set of bowls, 4/- for a weekly ticket, and 2d for the hire of rubber shoes (rubber slips were not permitted). By the following year, two dozen iron deck chairs had also been placed in the enclosure, available for hire to members of the public. A reminder that the green was always intended as a shared community space as well as a sporting venue. Half a century later, local characters Popeye and John would find their own free seats on the bowling green wall.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D-DS-206-251)

6. Etching of Cambridge Road and the land that became the nursery

This early etching shows Cambridge Road, laid out as part of the new Clifftown estate designed in the 1850s by architects Banks and Barry. At that time, the surrounding land was still awaiting development and was later occupied by Young’s Nursery before becoming the site of Alexandra Bowling Green. What began as part of the Victorian vision for Clifftown would, decades later, evolve into a space that has been central to community life for a hundred years.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Adrian Green)

7. Prittlewell Square (c1910)

Prittlewell Square, opposite the bowling green on the cliff top, is the oldest park in Southend, opened to the public in 1883. Designed with diamond-shaped paths, central pond and fountain it offers views across the Thames Estuary. The layout has changed little since the 1930s. More ornamental than the bowling green, it reflects another side of Clifftown’s tradition of open spaces for leisure, enjoyed by both residents and visitors alike.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Essex Record Office D-DS-206-246)

8. Alderman Parren and the Parren Shield (1930)

Alderman Parren, a founding member of Alexandra Bowls Club, played a leading role in promoting bowls across Southend. In 1930 he helped establish the Municipal Greens Association, created to encourage competition between local clubs. That same year he presented the Parren Shield, awarded annually to the winners of the Parren League. Now run by the Southend Parks Bowls Circle, the competition continues to be played today. A living link between the green’s early years and its centenary celebrations.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

9. Presidents day (1991)

Alexandra Bowls Club was founded in 1925 and played its first full season the following year, with 10 matches against other teams. Council records note early discussions about how many rinks were required, with a compromise of two eventually agreed. Mr. S. Spencer, Secretary of the Southend-on-Sea Bowling Tournament, also requested permission to hold a tournament at the green in July 1926. This photograph of President’s Day in 1991 reflects the club’s enduring success, providing both social and competitive opportunities for members and visitors alike. From its earliest matches to the present, Alexandra has remained at the heart of Southend’s bowling community for nearly a century.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

10. The Knitting Circle (1981)

This 1981 photograph shows Club President A. F. (Bert) Hodges with members of the Knitting Circle. Made up of the wives of Alexandra bowlers, the group gathered at the green not only to support their husbands’ matches but also to knit for charity. Their presence reflects how the club was more than a sporting venue: it was a social hub where friendships flourished, laughter was shared, and community spirit was woven together, stitch by stitch.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

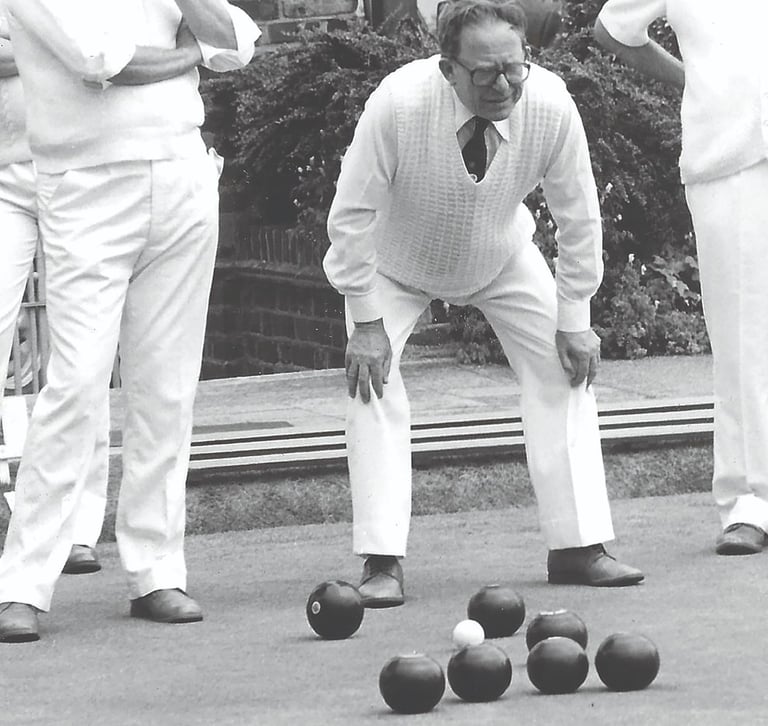

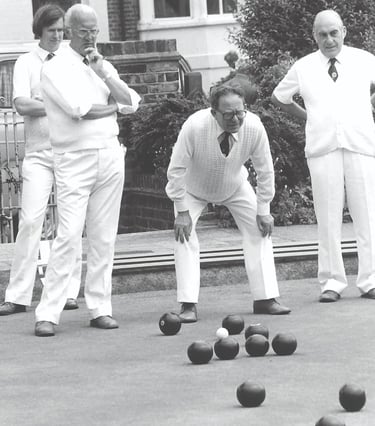

11. Assessing the State of Play (late 1980s - 1990)

This photograph captures a Saturday league match at Alexandra Bowling Green in the late 1980s or early 1990s, with club members Charlie Mead and Charlie Ronson pictured on the left. League fixtures were a regular feature of the club calendar, bringing together players from across Southend in friendly but competitive rivalry. For members, these matches were as much about camaraderie as competition, moments of shared focus, quiet skill, and the simple pleasure of the game. Such matches form part of a tradition that has continued for a century at Alexandra.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

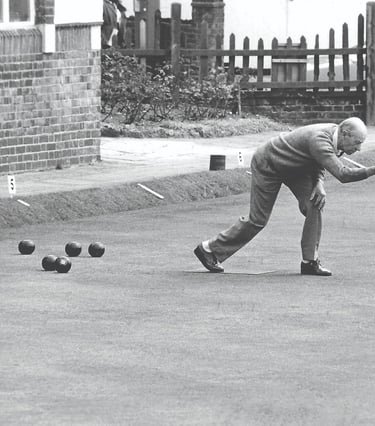

12. And we are bowling... (1974)

While seating for spectators was provided when the bowling green opened, protection from the elements was overlooked for the first ten years. In 1935, Messrs. Elam & Sons of Southend supplied a canvas shelter measuring 20 by 12 feet and 6 feet 6 inches to the eaves, with a canopy at the front, at a cost of £23 5s. Erected on the south-west side of the green, its position soon prompted complaints from a resident of Cashiobury Terrace. One likely candidate was Peter Alfred Clark of No. 4, a foreman at Warner & Co. India Rubber Manufacturer. A compromise was reached, and before the 1936 season the shelter was relocated to the north-east corner of Prittlewell Square. By the time of this 1974 photograph, such small adjustments had helped ensure the green was firmly embedded in community life. A story still unfolding a century later.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

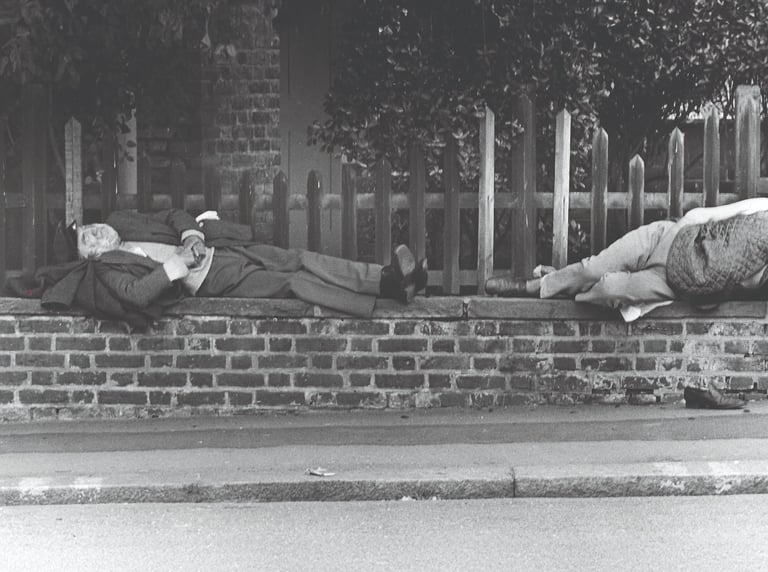

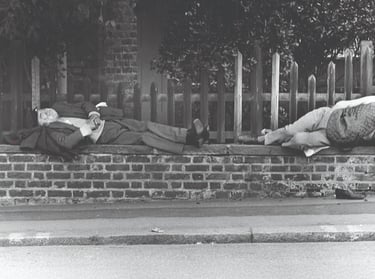

13. Tommy ‘Popeye’ Poppins and John Brookes taking it easy (1983)

By the 1970s and 80s, two familiar figures often seen around the Conservation area were John Brookes and his companion Tommy ‘Popeye’ Poppins. Fond of a drink but never causing real trouble, they were part of the fabric of local life resting on benches or walls, and here finding a spot on the bowling green wall itself. Popeye was known to entertain children for a few pennies with his tuneful rendition of “I’m Popeye the Sailor Man,” complete with a stick-and-cork ‘pipe’.

Their antics became part of local folklore. On one Saturday afternoon shopping trip, John was escorted down the High Street by two policemen completely unaware that his string-tied trousers had slipped to his ankles. As the policemen struggled, the watching crowd erupted into laughter, a memory still retold with fondness today.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society. Memory shared by Jo Clark)

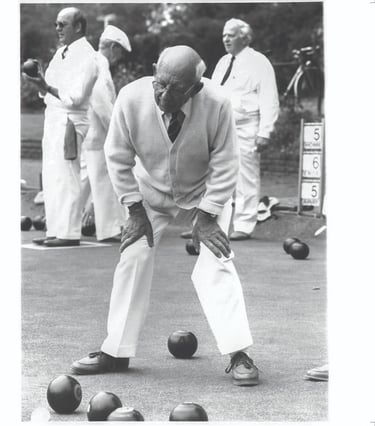

18. Lady Bowlers (c1990)

Historical records suggest that bowls has always been enjoyed by both men and women even Shakespeare makes mention of it. The rules, first formalised in Scotland, were the same regardless of gender.

In the modern era, however, the game developed along separate paths. The English Bowling Association was formed in 1903, followed by the English Women’s Bowling Association in 1931. For much of the 20th century, leagues, competitions and clubs were single-sex. By the 1990s, mixed clubs had become the norm, and in 2008 the national governing bodies amalgamated under the new title of Bowls England.

This photograph celebrates the women who played at Alexandra Bowling Green.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

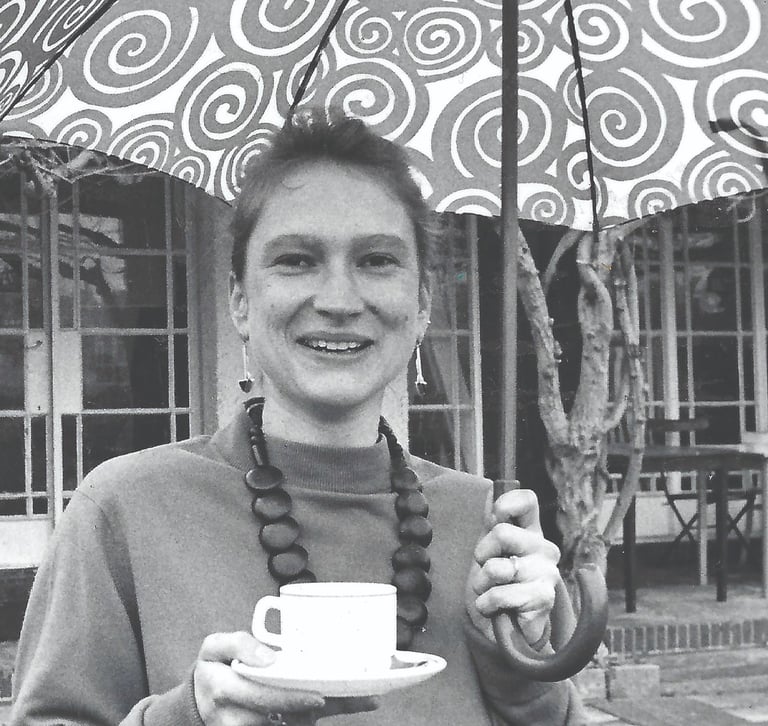

14. Refreshments at the Bowling Green 1991

Refreshments have been part of the bowling green experience since 1925, when Miss Cleave became the first proprietor of the café. Over the years it has remained a popular spot, praised in 1991 by the Southend Standard as serving “the best value cuppa in Southend.” A cup of tea has long been part of the ritual of bowling here, a pause between ends, a chance to chat with friends, or simply to enjoy the view. In the 1930s, visitors could even take their tea on the pavilion roof, adding a touch of novelty to this timeless tradition.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

15. A Key Turning Point: Alexandra Bowling Green in WWII

Bowling carried on during the war years, but members had to adapt to new realities. Sandbags and an Air Raid Precaution Warden’s (ARPW) post were positioned in front of the pavilion terrace, cutting into the café’s seating area. The licensee of the pavilion even complained of a loss in takings as a result. The ARPW also commandeered the greenkeeper’s room, prompting the Emergency Committee to contribute towards the provision of a temporary hut, eventually built on the south-west corner of the green, just as the club had first suggested. By September 1940 the café had closed and the facilities were taken over by the Auxiliary Fire Service stationed in Cambridge Road.

Perhaps the greatest change came when the boundary railings were removed for the war effort, part of a nationwide campaign to reclaim iron for munitions. Their absence left the green exposed to damage by dogs and children, and wooden fencing was brought in from Thorpe Esplanade as a temporary measure. The loss of the original railings was keenly felt, and today Clifftown Conservation Society, with support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, is working towards their restoration, reconnecting the green with its pre-war character.

Through all these disruptions, bowlers continued to play, keeping the spirit of the club alive in the most difficult of times.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

16. Bowling for All: From Season Tickets to Roll-Ups

By the 1930s, bowling was growing steadily in popularity. Until then, players had to buy a ticket for a specific green, but in 1932 the Town Clerk changed the system, introducing a season ticket that allowed play on any of Southend’s municipal greens. Charges rose to 35 shillings, and opening hours were set from 2pm to dusk on weekdays, with longer hours on Saturdays and bank holidays. Some even wrote to the council asking for morning play to be introduced!

This photograph, taken in the early 1990s, shows two bowlers enjoying an informal game — cigarette bins placed neatly at the end of each rink. It’s a reminder that, whether through official matches or friendly roll-ups, the green has always been a place where people came together simply to play.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

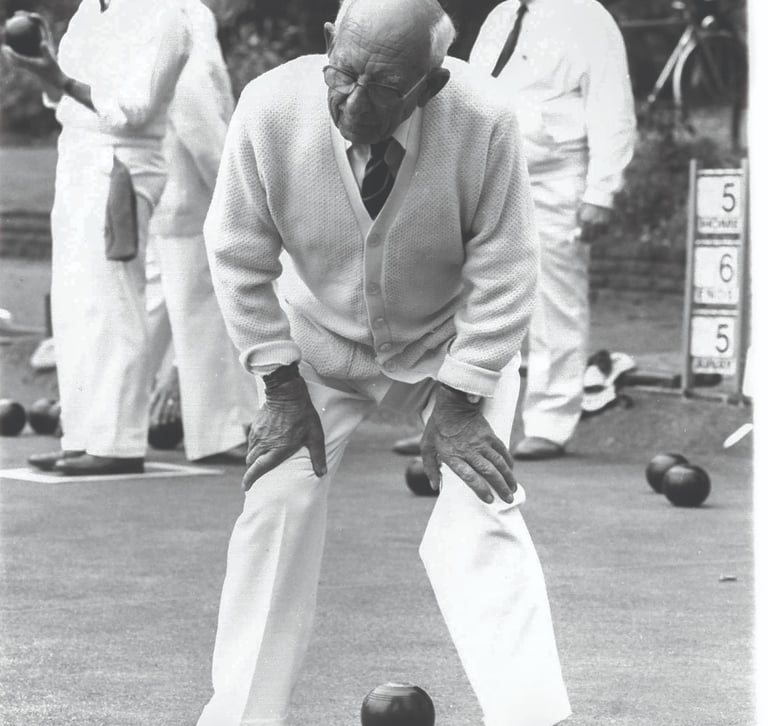

17. An increasingly Popular Sport

As bowls grew ever more popular, the game was shaped by the dedication of its long-term members. Bert King, Club Captain between 1984 and 1988, was one such figure. Away from the green he managed the presses of the Southend Standard newspaper, but here he was remembered for his leadership and his love of the game. Figures like Bert helped carry the club forward towards its centenary.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Alexandra Bowls Club)

19. Celebrating the Centenary of Charter Day 1992

On 5 August 1892, Queen Victoria granted Southend its Royal Charter, and the document was formally delivered the following month on 19 September. The Charter gave Southend County Borough status, marking a turning point in the town’s growth and identity. A century later, in 1992, the anniversary was celebrated in style, as shown in this photograph. Civic pride has always run alongside leisure in Southend, with many bowlers, including founding figures like Alderman Parren, deeply involved in the life of the town.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

20. Man in the Fountain 1988

Prittlewell Square originally featured a rockery at its centre, before the pond and fountain were added in the 1930s. By the 1980s, the fountain was drained for repairs, briefly transforming it into a sheltered suntrap. One local George Rohzeder took full advantage, settling into the empty basin with his newspaper. Certainly more comfortable than a rockery.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

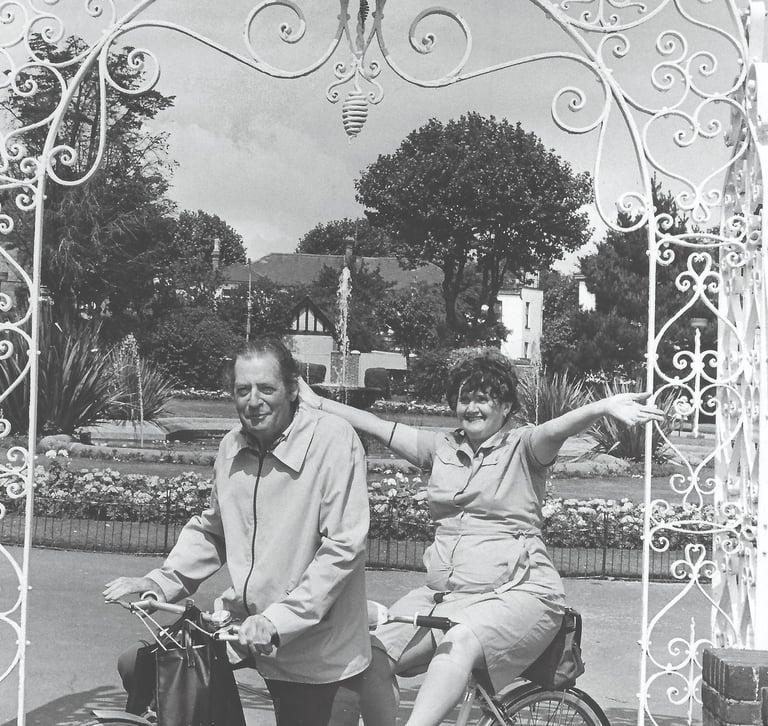

21. Tandem Bicycle 1982

The main entrance to Prittlewell Square is marked by its ornate wrought-iron arch, topped with a clock donated by local jeweller and philanthropist R. A. Jones. When Geoffrey and Hilda Hallett pedalled through on their tandem in 1982, the clock happened to be away for repair. No matter, their visit shows that, in Clifftown as on the bowling green, time flies… and this centenary reminds us just how quickly.

(Image reproduced courtesy of Southend Conservation Society)

Time-Lapse Pinhole a Project by

Tom Scott

The bowling green video was shot using time-lapse with a pinhole attached to the digital camera instead of a glass lens. Over a number of weeks l would set the camera facing the cafe, looking west to the two large trees and other vantage points around the green. Hoping for sunny days and wind. A number of bowling matches were also shot.

The video illustrates the calm environment of the green, the activities around the cafe and the games as well, all mediated through the pinhole giving a softness to the image as well as the time lapse altering the motion.

"Wait, hang on! let's dig a bit deeper, other things happened, people chatted to me enquiring about the camera, passing the time of day, l became a resident so to speak of the green for those few weeks, the life and rhythm of the cafe became apparent as l sat and gazed over. The lone thinker marching round the green. The ‘regulars’ on their benches, all that and more was observed as well as the trees moving, the sun casting shadows, the clouds drifting in the sky, the birds pecking the green. All felt well with the green." Tom Scott

The Bowlers

The Pavilion

Clifftown Soundscape

by Lex Bartlett

A Soundscape that captures the essence, history and cherished memories of Clifftown, created from interviews with local residents and historical researchers. These conversations offer valuable insights into their perspectives on the area, while recounting fascinating stories and personal experiences that illustrate the neighbourhood’s vibrant character. With the gentle clinking of bowls, the lively chatter of voices, and the soothing rhythm of waves, creating a captivating backdrop. As a resident of Southend, it has been a privilege to explore the vibrant community and rich history of Clifftown. Known for its Victorian architecture and stunning coastal views, this charming neighbourhood offers a unique story, with each interaction deepening my appreciation for its heritage and the spirit of its residents.

A heartfelt thank you to everyone who took part:

Andy & Joan, Colin Cooper, Derek Reader, Joe Scotland, Phil Cannell, Peter Bowen, Penny Lowen, Richard Brown, Richard Hopson

Sample Soundscape

Full Soundscape

Contributors

The Clifftown Conservation Society would like to thank for their contributions;

Photograph permissions

Alexandra Bowls Club

Essex Record Office

Southend Museums

Southend Conservation Society

Cheryl & Emma Masterson

David & Val Kitchiner

Garry Stone

Indigouk

Keith Brooker

Colin Cooper

Artefact Donations/ Information Input

Adrian Green

Derek Reader

Peter and Margaret Stainer

Linda Donlan

Jo Clark

Art work interpretations

Emma Bell

Paula Pavitt

Tom Scott

Angelina Mounsey

CCS Research Team

Colin Cooper

Emma Cannell

Lex Bartlett

Michael Hickie

Peter Bowen

Phil Cannell

And everyone who contributed to our audio soundscape project

Exhibition text and original research © Clifftown Conservation Society (2025). Digital media by Tom Scott and Lex Bartlett. This original content is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund and shared under a CC BY 4.0 license. Please note: This license does not apply to the historic photographs listed in the permissions above, which remain All Rights Reserved by their respective owners.